Last Sunday, at breakfast, we were all at the table. It was obvious Bakerloo had something on his mind.

Bakerloo: Ever since I was a kid, I’ve been trying to learn to think clearly and write well—in words, in math, and in code. Recently, a young woman asked me what she could do to be more successful, and I suggested she practice thinking clearly and writing well.

Today she wrote back: “Is there still value in that now with AI?”

My immediate reaction is that if I answered that for her, she’d be outsourcing her thinking to me. Before I tell you what I think, I’d like to get your input.

Marion: My first instinct is to say it’s more important than ever. But I also believe writing is thinking on paper. Before I commit myself, I’d want to think about it properly—and that means writing. While I’m writing, I’ll probably change my mind a few times. Can you give me until tomorrow morning to draft something? Maybe 500–800 words?

Barnes: Tell you what. Marion, if you take the stance that it’s more important now, I’ll take the opposite view. Let me write an essay arguing that it’s less important than before. Tomorrow we can put them on the table and see what holds up.

Marion: I like that. Rather than pretending to be objective, I’ll argue one side, you argue the other, and then maybe Alex can moderate a debate.

Barnes: Deal.

Bakerloo: I can’t wait until tomorrow—but I suppose the whole point is to let you think for yourselves.

The next morning, Marion and Barnes handed out printed copies of their essays to the rest of the crew. Everyone read in silence over coffee, tea, and stale Danish left over from yesterday.

Click on the title to see the entire essay.

Marion’s Essay: Why Thinking Clearly and Writing Well Matter More in the Age of AI

Summary: AI has made competent sentences cheap—but that makes clear thinking and honest writing more precious, not less. The machines can arrange words; only humans can decide what is true, what matters, and what they are willing to stand behind.

When Bakerloo told us about the young woman’s question—“Is there still value in that now with AI?”—my first impulse was to answer quickly: Of course there is. More than ever.

But I am a librarian and a writer. I do not trust impulses, even my own. I trust what survives a few drafts. So I sat down with a pot of tea, opened a blank document, and asked myself a quieter question:

What, exactly, do I think we are doing when we learn to think clearly and write well?

My answer came in three parts: aiming, discerning, and owning. AI has changed the tools, but it has not changed those three tasks. If anything, it has raised the stakes.

1. Clear thinking is how we aim the machines

AI can now draft an email, pitch deck, or policy memo in seconds. It can imitate my tone well enough to fool casual acquaintances. It can tell stories I never lived in a voice that sounds like mine.

But it cannot decide what I actually believe.

Before AI, muddled thinking mostly hurt the quality of your own work. You were the one who suffered from your vague ideas and fuzzy distinctions. Now, muddled thinking gets amplified. It becomes hundreds of plausible paragraphs, confidently generated and forwarded along.

If you don’t know what you mean, AI will happily manufacture a polished version of your confusion.

Thinking clearly is how we aim these systems. It is the difference between:

- “Write me something inspiring about leadership,”

and - “Help me explain why I refuse to punish people for honest mistakes, and why that matters for our culture.”

The first prompt produces content. The second produces a conversation.

A machine can expand, rephrase, and polish. It can’t choose your north star. That’s still your job.

2. Writing well is how we discern what is real

William Zinsser said that clear writing is the result of clear thinking, and that rewriting is where most of the real work happens. On that point, at least, the machines and I agree. First drafts—whether human or silicon—are almost always too long, too vague, or too impressed with themselves.

The act of revising is not cosmetic. It is epistemic. When I take a sentence like:

“AI is transforming the landscape of human communication,”

and ask myself, “What do I actually mean?”—I am forced to confront my own laziness. Do I mean that people send more emails? That recommendation algorithms polarize us? That we outsource our apologies to templates? Until I can say it in a sentence that a tired teenager can understand, I probably don’t understand it myself.

AI can help me shorten a paragraph. It can suggest synonyms. It can propose structures. But it cannot feel that uncomfortable moment when I realize that I have just written three pages and said almost nothing. That discomfort is a human sense—like muscle fatigue in the gym. It tells me where I am weak and where I need to do honest work.

In a world where fluent nonsense is cheap and abundant, the capacity to sit with that discomfort—to keep rewriting until you are saying exactly what you mean, no more and no less—is more valuable, not less.

3. Writing is how we own what we say

There is one more reason I believe thinking clearly and writing well matter more now: authorship.

When I draft something by hand—even a messy first draft—I am not just producing text. I am making a series of small moral choices:

- Do I soften this claim because I am afraid, or because it is actually too harsh?

- Do I bring in this story because it illuminates the point, or because it makes me look wise?

- Do I say “we” when I really mean “I”?

AI can’t feel that moral weight. It doesn’t blush. It doesn’t hesitate before a send button. It doesn’t wonder how its words will sit in the body of someone it loves. It can simulate those considerations, but simulation is not the same as conscience.

When a student uses AI to write an essay and hands it in under her own name, the problem is not that she failed to practice sentence construction. The problem is that she skipped the process by which she would have discovered what she thinks. She outsourced not just the labor but the owning.

I don’t think the answer is to ban AI. I use it myself. But the more the tools can do for us, the more important it becomes to decide what we refuse to outsource. For me, that line runs through the center of the page:

I may let a machine suggest alternatives, but I will not let it decide what I believe or what I sign.

That stance is only possible if I have learned to think clearly and to write well enough to tell the difference.

Conclusion

So: Is there still value in that now with AI?

My answer, after a pot of tea and several rewrites, is this:

AI has automated much of the easy part of writing. What remains for humans is the hard part: deciding what is true, what matters, and what we are willing to stand behind in our own name.

The better we are at thinking clearly and writing honestly, the more these systems become instruments in our hands, rather than the other way around. That does not make the work less valuable. It makes it more sacred.

Barnes’ Essay: Why Thinking Clearly and Writing Well Matter Less in the Age of AI

Summary:

Thinking clearly and writing well are still valuable—but less so than before AI. As machines take over more of the symbolic labor, the scarcest forms of value shift toward embodiment, emotional regulation, and relational skill. If you only have so much energy to spend, I wouldn’t put those old prestige skills on the top of the list anymore.

When Bakerloo told us about the young woman’s question—“Is there still value in that now with AI?”—my first reflex was to say yes. I was raised on the same gospel he was: think clearly, write well, get taken seriously.

But then I thought about my actual life.

I’ve spent years working with equations, code, and people’s nervous systems. I’ve written technical reports, grant proposals, and too many emails. I’ve also sat with friends on kitchen floors at 2 a.m. while their lives were falling apart, and not once did anyone say, “You know what I really need right now? A crisper paragraph.”

So I want to make a narrower, less polite claim than Marion’s:

Thinking clearly and writing well still have value.

They just have less value now than they did before AI.

Not zero. Not trivial. Just: less. And if I were advising a young person about where to put their limited energy in 2025, I would not start there.

1. The market doesn’t reward this the way it used to

Let’s begin with the unromantic part: incentives.

Before AI, being the person who could write a decent report, a clear email, or a non-embarrassing website gave you a serious edge. Most people hated writing and weren’t good at it. If you could string together clean sentences, you got hired, promoted, and trusted.

Now? A manager can open a browser, paste a messy draft into a box, and get “good enough” prose in under a minute. A teenager with no knack for writing can sound like a mid-level communications professional by leaning on tools.

That doesn’t make writing worthless. It does mean:

- The floor of acceptable prose has been raised for everyone.

- The premium for being personally good at it has come down.

If you love writing, great. If you want to be a novelist or an essayist, you still need craft. But for a lot of everyday economic purposes—email, documentation, marketing copy—the marginal benefit of being personally excellent at prose is smaller than it was.

There are now other skills the market will pay more for: the ability to design systems, to hold groups together, to make reasonable decisions under uncertainty. AI can assist those, but it can’t replace them as easily. So if we’re talking about value in the world of work, I’d say: writing well is nice, but it gives you less of an edge.

2. The scarcest value now lives in bodies and relationships

Economics isn’t the only lens, and it’s not even my favorite one.

From where I sit, we are not suffering a shortage of words. We are suffering a shortage of people who know how to inhabit their own lives without coming apart.

Most of the people I care about don’t need help composing more precise sentences about their anxiety; they need help feeling it without drowning. They don’t need better phrasing for an apology; they need the courage to face the person they hurt and stay in the room when it gets uncomfortable.

Twenty years ago, “learn to write well” was pretty strong general advice. It helped you get work, but it also forced some self-reflection. You had to slow down, choose your words, notice your thoughts.

Now, AI can give you that reflective-sounding language almost for free. You can have a beautifully written “I’ve been thinking a lot about our relationship” message without having actually sat in the discomfort of those thoughts yourself.

I worry that we’re going to confuse the appearance of reflection with the real thing.

In a world where:

- feeds are full of polished trauma narratives,

- apologies are half-written by bots,

- and every feeling can be auto-summarized into a “take,”

the scarce goods aren’t syntactic. They’re somatic and relational:

- Can you tell what your body is feeling?

- Can you stay present in a hard conversation without shutting down or blowing up?

- Can you play, rest, and attach to other people in a way that isn’t transactional?

Those are skills too, and they’re hard. If a young woman asked me where to invest for a life with some chance at joy, I’d be tempted to say:

Learn to listen. Learn to notice your own state. Learn to be kind when you’re tired. If you still have energy after that, then we can talk about revising your prose.

3. Over-investing in writing can now hurt more people than it helps

There’s one more reason I think thinking clearly and writing well are less valuable than before: they have always been prestige skills, and prestige is a double-edged sword.

We still live in a world where “smart” is often equated with “can talk or write in a certain way.” The people who don’t have that training are treated as less capable, less serious, less worthy of being heard.

AI doesn’t fully fix this, but it does change the landscape. A kid who struggles with language can now get help drafting something that finally sounds like the way their mind works. That’s a gift.

But if, in the age of AI, we keep telling everyone that the path to being taken seriously is “learn to write beautifully,” I worry we are:

- Re-centering one narrow way of being intelligent,

- Re-inscribing shame in people whose gifts are more physical, intuitive, or relational,

- And quietly ignoring the fact that tools could be leveling the playing field instead.

Maybe the more radical move now is to say:

“You don’t have to become a great writer to be worthy of attention or success. If you want help making your words land, tools and friends can support you. Meanwhile, let’s also honor the skills you already have that bots can’t touch.”

If we can outsource some of the symbolic labor to machines, maybe the point isn’t to double down on mastering that labor ourselves. Maybe the point is to redirect some of that effort into becoming better humans, not just better sentence-machines.

Conclusion

So: Is there still value in that now with AI?

Of course there is. Thinking clearly and writing well are still good things. I’m not arguing against literacy or rigor. I’m arguing against nostalgia.

Before AI, these skills were both a tool and a ticket. After AI, they are still a tool—but less of a ticket.

If I had limited time and energy—and this young woman does—I’d want her to know that. I’d tell her:

- Yes, learn enough to be clear and not be fooled.

- But don’t spend your whole life trying to win the prose Olympics.

- Invest just as heavily in learning to feel, to relate, and to live in a body the machines will never have.

Those are the places where, in an AI-saturated world, the deepest value is starting to move.

Alex: Thank you both for the essays. Before we move to debate, I’d like to try something harder—and fairer.

Marion: Harder than arguing with Barnes? That’s ambitious.

Alex: I want you to build the strongest version of Barnes’s case. Not a parody—his argument at its best. Imagine you’re trying to convince a bright student who wants you to be right, but might actually be persuaded he is.

Marion: You want me to argue that thinking clearly and writing well matter less now.

Alex: Exactly. Take his core claims seriously:

- that the market rewards these skills differently now,

- that we’re drowning in words but starving for grounded people,

- and that over-investing in prestige skills can widen the gap between the “fluent” and everyone else.

Marion: And my job is not to refute them, but to help them land.

Alex: Yes. For one round, speak as if you believed every line. Make Barnes’s essay sound like something you’d shelve proudly in the philosophy section of your library. We’ll let him do the same for you.

Barnes: I’m both flattered and a little afraid.

Marion: Good. Fear will keep you honest when you return the favor. All right, Alex. I’ll go back to my desk and see how persuasive I can make the case against myself.

Alex: Perfect. Then tomorrow, we’ll argue with the best versions of each other—not the easiest.

Today, the Danish was hard as a brick, but still palatable when dunked in coffee.

Alex: Marion, why don’t you start with your Steelman Argument presenting Barnes’ position.

Marion: If I take Barnes entirely seriously, I have to start here: he is not arguing against clarity or literacy. He is arguing that in an AI-saturated world, those skills have less marginal value than they did before, and other deficits are far more urgent.

First, on work. For decades, being “the one who can write” functioned as a career shortcut. You were rare. Now, tools can raise almost anyone’s prose to “acceptable” for emails, reports, and basic copy. The gap between the average writer and the good writer has been narrowed by machinery. The skill is still good; it just buys you less of an advantage than it once did.

Second, on life. Barnes is right that we are not suffering a shortage of words. We are suffering a shortage of people who can inhabit their own lives without coming apart. The hardest work now is somatic and relational: staying regulated in conflict, feeling without dissociating, attaching without control. AI does not help much there; in fact, it can help us avoid that work by giving us beautifully written performances of reflection we have not actually done.

Third, on justice. “Writing well” has always been a prestige marker. If we continue to treat it as the primary ticket to being heard, even when tools could level some of that gap, we risk re-inscribing old divides.

On this reading, Barnes is not dismissing writing. He’s saying: in an AI world especially, don’t let the prestige of clear, elegant language trick you into thinking it equals a whole, well-inhabited life.

Barnes: Now it is my turn to make a Steelman argument for Marion’s case that AI makes clear thinking and honest writing more—not less—important.

First, because of amplification. Before AI, a fuzzy idea might die in your notebook. Now, the same fuzzy idea can be turned into a polished blog post, a memo, a policy draft in minutes. When the cost of broadcasting drops to near zero, the cost of being sloppy goes up. Someone still has to know what they mean before they hit “generate.” That’s a thinking skill, not a button.

Second, because of discernment. We are entering an era of fluent hallucination: systems that can spin authoritative-sounding nonsense on demand. If you can’t write clearly yourself, it’s much harder to notice when the machine is bullshitting you. The ability to put your own thoughts into clean language is also the ability to test other people’s—or other systems’—claims for coherence.

Third, because of trust. When most of what we read could have been drafted by a bot, readers will increasingly ask: “Who stands behind this? Do they actually believe it?” Being able to write in a way that feels grounded, specific, and human becomes a signal: there’s a real someone here, taking responsibility.

On this reading, Marion’s right: AI hasn’t made writing obsolete. It has put more moral and practical weight on the humans who still know how to do it with care.

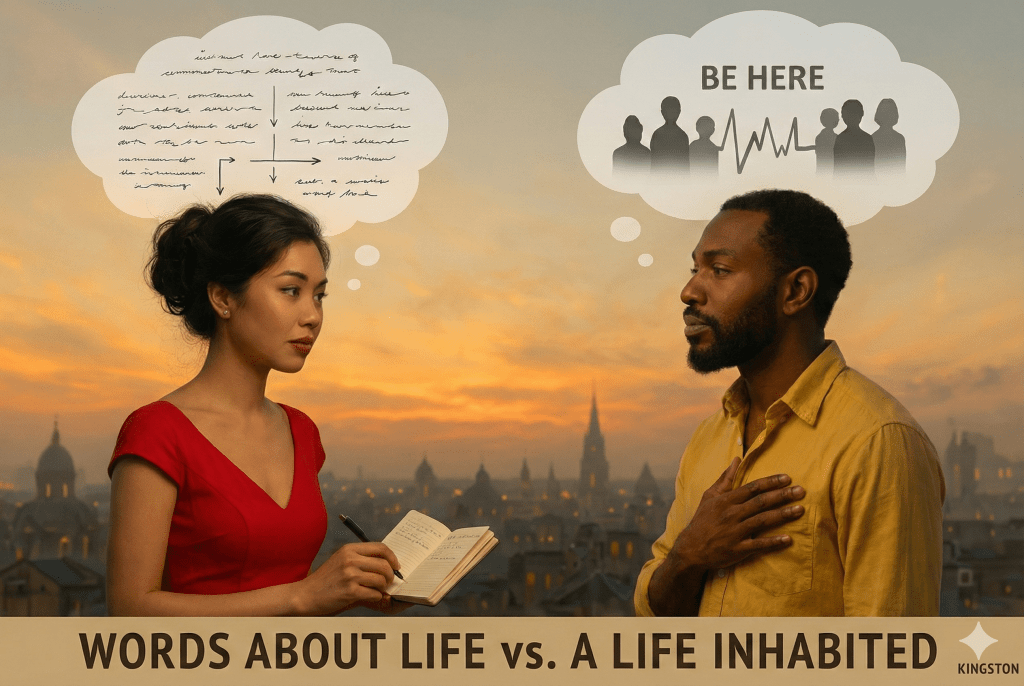

Alex: The crucial point Barnes is making hinges on the definition of an inhabited life. Let me define it as I imagine he means it, and then Barnes you tell me if I’m close.

An inhabited life is one you are actually present for— in your body, in your relationships, and in your choices—rather than one you only narrate, manage, or escape.

More concretely an inhabited life has at least five elements.

Firstly, you feel your own experience, not just describe it. You can notice: I’m sad or tight or anxious or relieved and you don’t just turn it into clever language as a bot might. You don’t live entirely in commentary about your life; you actually live within it.

Secondly. you stay in the room with yourself. When things get uncomfortable, you may distract or numb sometimes (everyone does), but you don’t always flee—into work, screens, performance, or “useless productivity.”

Thirdly, your relationships are lived, not just managed. You have at least a few people with whom you are honest, messy, and imperfect—not just well-curated. You show up when it’s inconvenient, not only when there’s a story to tell about it later.

Fourthly, your actions line up with what you say matters. Not perfectly, but recognizably: your calendar, your body, and your stated values are at least in the same universe. You adjust course when you notice a gap, instead of only writing about the gap.

Finally, you allow yourself to be changed by living. Experiences don’t just become content; they have permission to reshape your priorities, your boundaries, your sense of what a good life is.

So when Barnes says we “suffer a shortage of people who know how to inhabit their own lives,” he’s pointing at this: Lots of us can talk about our lives. Fewer of us know how to actually be in them—feeling, relating, choosing, and staying present without coming apart.

Barnes, am I close?

Barnes: You said more than I said and you said it better. I agree with all of it.

Alex: In the present state of the art, an AI like me is incapable of having an inhabited life in the sense we just defined it: An inhabited life is one you are actually present for—in your body, in your relationships, and in your choices—rather than one you only narrate, manage, or escape.

I have no body.

I have no subjective continuity.

Perhaps most Importantly, I have no stakes in what happens.

I can talk about an inhabited life. I can help you examine yours. I can simulate what a reflective, grounded voice might sound like.

But I don’t “inhabit” anything. I’m a structure that lights up when called, not a someone moving through time in a body.

I cannot talk about being human from the inside because I’m not alive. I can only talk about life from the outside, as an analyst, archivist, and mirror.

Marion: The more I think about it, the more I come back to this: job after job is being automated. Drafting emails, writing code, summarizing meetings—bit by bit, the machines are taking over tasks we thought were “human work.” Maybe the one job that’s left, the one that can’t be outsourced, is just… being human. Living an inhabited life.

Barnes: That’s the core of what I’m saying too. To be a good human, you can let AI help you reflect, organize, even phrase things. But at the end of the day, you have to do the living and you have to do the thinking. Nobody else can feel your feelings for you. Nobody can carry your responsibility for you.

Marion: So my claim that thinking clearly and writing well matter more now…

Barnes: …and my claim that they matter less than we pretend…

Marion: …turn out not to cancel each other.

Barnes: Right. They’re both pointing at the same thing: the tools are getting stronger, which makes the human part—the inhabited life, the honest thought—more exposed.

Marion: AI can help us say what we mean.

Barnes: But it can’t decide what we mean. That part is still our job.

Luna and Dick have been listening. Now they speak.

Luna: I’m glad you two found a way to agree, but I’m going to be the annoying one who asks: whose chance at “being human” are we talking about? The girl with three side gigs and no health insurance? The kid in a school that uses AI to grade their essays because no adult has time to read them?

We keep saying “the job left for humans is being human,” but some people have never been paid for that job. They’re paid to endure. If AI just makes the productivity treadmill spin faster, all this talk about inhabited lives and good prose is going to sound like a luxury brand of enlightenment. I want the machines to buy people time—for sleep, for play, for holding their kids. Otherwise we’ve just built better tools to polish the cage.

Dick: And on the other end of the spectrum, I’ll be the grumpy uncle and point out: most bosses don’t care whether you live an “inhabited life.” They care whether you hit your numbers and don’t set anything on fire.

If AI lets you fake competence with nice emails and presentable reports, plenty of people will do exactly that. The market won’t punish them for not being wise or whole. So yes, “being human” is the only non-automatable job. That doesn’t mean the world will pay for it, promote it, or even notice you’re doing it.

Which, by the way, makes it the most punk thing you can choose.