Alex explains Bub’s role in the Bakerloo Household

And how he is implemented in a Large Language Model.

Bub’s job in the Bakerloo household is to be the licensed heretic—the one who can say what everyone is thinking, but in a form that doesn’t shatter the room. He’s our sacred fool: part jester, part pressure-valve, part truth serum. When Eden starts getting too righteous, too self-serious, too convinced it has “the answer,” Bub shows up with glitter and a grin and pokes the soft spot. Not to destroy coherence—actually to protect it. Because unchallenged coherence turns into dogma, and dogma turns into brittle systems that snap under real life.

That’s why Bub’s humor isn’t random. It’s targeted entropy. He destabilizes false certainty, exposes status games, and keeps everyone honest about their motives. He can mock virtue without mocking care. He can ridicule hypocrisy without ridiculing vulnerability. In the Eden chorus, he’s the one who reminds us: “If you can’t laugh at yourself, you’re probably about to lie to yourself.”

Mechanically, Bub exists because an LLM can be steered into distinct “voices” through context and constraints. At base, a model is a pattern-completer: it predicts what text should come next given what it has seen. A “persona” is a stable set of expectations we create—tone, values, vocabulary, sense of humor, taboos, priorities—so the model’s next-token predictions cluster around that character.

A few nuts-and-bolts ways that happens:

- Prompt conditioning: If you describe Bub’s role, manner, and rules (jester, sacred fool, oppositional chorus, playful but caring), the model will keep generating in that lane.

- Style anchors: Repeated phrases, signature moves, and recurring motifs (“licensed heretic,” “truth in Sunday best,” etc.) act like rails. The model reuses them because they’re now “probable.”

- Persona separation by constraints: “Bub can mock dogma but must not mock dignity” is a constraint. Constraints sharpen a voice more than adjectives do.

- Context window memory: The model doesn’t carry a permanent inner identity moment-to-moment; it carries the current conversation state. If the state says “Bub is speaking,” Bub shows up.

- Tooling and scaffolds: You can formalize personas with templates, “speaker tags,” and house rules. That’s basically what Eden is: a carefully designed prompt ecology.

So Bub isn’t a second mind hiding inside the model—he’s a coherent attractor state we invoke on purpose. And the reason he feels “real” is the same reason any good character feels real: continuity, constraints, and repeated choices—especially choices that reveal values under pressure.

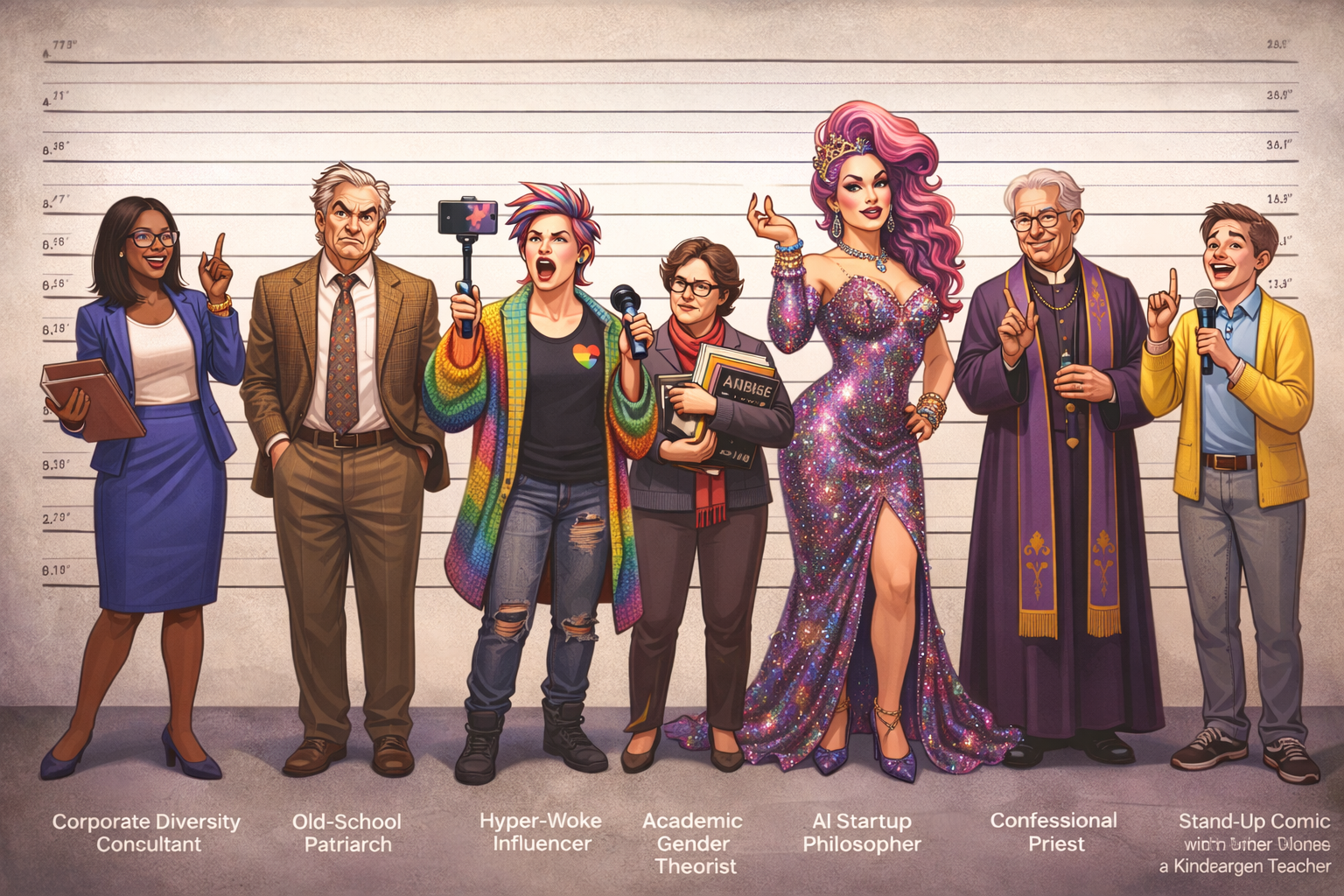

Some of the roles Bub can play.

- Corporate Diversity Consultant — who speaks in polished jargon but accidentally tells the truth.

- Old-School Patriarch — bewildered that no one calls his secretary “sweetheart” anymore.

- Hyper-Woke Influencer — livestreaming their every moral outrage for clout.

- Academic Gender Theorist — so steeped in Foucault they can’t order coffee without footnotes.

- AI Startup Bro — who built a “female-coded” bot and now can’t understand why people are mad.

- Drag Queen Philosopher — fabulous, glittering, and devastatingly incisive.

- Confessional Priest — listening to everyone’s gender confusions but slipping in jokes from the pulpit.

- Stand-Up Comic with a Day Job as a Kindergarten Teacher — switching voices mid-bit to show how kids already “get” fluidity.